Iraq Jordan Palestine

Marina of Beirut, Lebanon

Marina of Beirut, Lebanon

Shortly after I left Miami, I started taking a jujitsu class in California, and one of the purple belts had a strange accent. I asked him where he was from and he said, “Lebanon.”

The bottom dropped out of my stomach. Here was a native of Ronan’s nightmare in the peaceful suburbs of California.

We became good friends during the spring, but I was hesitant to ask him too many questions, and he rarely answered with identifiable nouns. Once he said that his family had been in a Lebanese port trying to catch a boat to France when the area, known to be crawling with civilians, was shelled by Syria. His family survived, but not everyone did. I told him I didn’t know how to think about things like that, or about what Ronan had told me. I had a hard time just phasing them out.

He said, “That’s because you haven’t lived through war. If I didn’t phase out some of the shit I saw over there, I’d be so fucked up right now.”

He said a bit later, sounding bored and tired of the subject, “There is never a reason for war. War is for money and power. That’s a well-known fact.”

He was my first friend from the Middle East, and through him I began to put a face on it, and some smells and tastes and sights with it, beyond the outrageous Western stereotypes. He was from the beautiful modern seaside city of Beirut and had a summer home in the forested mountains inland. The way he talked about Lebanese food and nightclubs and universities and women blew all my preconceived notions out the window.

I made another friend, a Croatian guy from Split who owned a posh wine bar in Palo Alto called Lavanda, named after the lavender of Hvar. He came into the pub where I worked one night. Just the mention of Croatia made me light on my feet.

I found out I would be stationed at a children’s summer camp in Southern Russia, not at all far from Lebanon, from June until August. I thought about cruising through Georgia and Turkey after that, maybe flying from Ankara to Beirut if I couldn’t get through Syria, and then taking a boat to Greece and going on from there. At the end I could visit Ronan in Ireland for Christmas.

In the middle of my planning, a friend from France contacted me and said he would have some vacation time at the beginning of September, and why didn’t we meet up somewhere?

I wrote to him:My visa in Russia will expire on September 13, and after that I would like to visit Turkey, Jordan (Petra!), Israel, Egypt, maybe Lebanon… I also want to visit Greece, Croatia again, and Italy at some point, and I may stop by France on my way to Ireland…

It was just a stream-of-consciousness random list of places, and he picked Egypt. I never would have, but I thought, what the hell. Tickets from Moscow to Cairo were surprisingly cheap, and I picked one up.

On my last day in southern Russia, I checked my email in an internet cafe and saw a note from Ronan with the subject, STILL FAR AWAY. My heart leaped and I melted with relief. I hadn’t heard from him in months. I kept running scenarios through my head of him being hurt or killed. I had a horrifying vision of making it to Ireland in December and visiting not him but his gravestone. I had no idea how I would even find out if something happened to him.

For now everything was OK again. He wrote:

DEAR PAMI emailed him back immediately and told him I wasn’t as far away as he thought, and I would be in the Middle East soon. He sounded sad and frustrated, and I hoped I could see him and cheer him up soon.

I AM VERY SORRY FOR NOT WRITING IN QUITE A LONG TIME BUT I HAVE BEEN AWAY, STILL AM AND WILL BE FOR A WHILE YET. YES YOU GOT IT I AM BACK IN THE SUNNY RESORT OF [a military base in] IRAQ. WONT BE ON DUTY FOR A WHILE THO CAUSE I GOT SHOT IN MY FAT ASS BY SOME NASTY IRAQI WITH AN ATTITUDE PROBLEM. IM OK BUT IT MAKES SITTING DOWN QUITE DIFFICULT AND THEY WONT SHIP ME HOME.

THE WEATHER IS NICE. HAVENT SEEN A RAIN SHOWER SINCE JESUS WAS A BABY AND THE WORST THING IS THAT THE SAND KEEPS GETTING IN MY BOOTS EVEN IN THE FIELD HOSPITAL. I HOPE ALL IS WELL WITH YOU AND YOUR FAMILY AND I STILL WEAR YOUR WATER SYMBOL AROUND MY NECK. IT KEEPS ME SAFE.

I GOTTA SIGN OFF NOW SO TAKE CARE. I DONT KNOW WHEN I CAN E-MAIL AGAIN BUT ILL SEE WHAT I CAN DO.

GOOD BYE

NEO x

A couple of months later I left Egypt and made my way to Amman, Jordan. I stayed at a hotel where foreign aid workers, journalists, human shields, and activists from Iraq and Palestine congregated. Partly to try to see Ronan, partly just to follow his example, I sought out a ride to Baghdad and was offered one for $200. I asked some reporters if my trip sounded wise.

Amman, Jordan

“Are you a reporter?” they asked.

“No.”

“Foreign aid worker?”

“No.”

They paused. “Then why do you want to go?”

I shrugged. “Just to see.”

They smiled at me, rather patronizingly, but for good reason. “Are you ready to see cars full of live people run over by tanks?”

I paled. “No.”

“Are you ready to see a busload of women and children killed because a mother reaches for a bottle and a teenaged American thinks it’s a grenade?”

I wanted to be sick. “No.”

“So what do you think? Is it a good idea?”

“No. Not at all.”

On October 12, after I’d heard too many stories like that from Iraq and Palestine, I wrote in my journal, my hands shaking:

Jesus I’m dizzy. I see it for myself, first-hand. I mean, I talk to those who have been there… There’s no doubt anymore of how coldly brutal the amiable folks on TV are to other people. No doubt my government lies and plunders. No doubt there’s another side to it all and they are real and they are rightly, impotently angry. And suffering.The next day I wrote to my family:

Marwan [a half-Palestinian German I met who had family in Jordan] said twenty years ago [in Jordan] people, women, were wearing shorts and minis, and people were happier and friendlier. Now the economy is in shambles and refugees are everywhere and people go back to old ways hoping it might help somehow, believing in something that can’t seem to do anything about the constant and brutal occupation. Turkey, Britain, America, all have had their way with this land.

[In 1921, British Lieutenant-General Sir Stanley Maude marched into Baghdad and said, “Our armies do not come as conquerors, but as liberators.” Within three years 10,000 Iraqis had died in an uprising against the British, who gassed and bombed the ‘terrorists’.]

The Arab leaders are just trying to stay afloat on changing tides and it seems like no one speaks for the people. Arts and cultures are exploited and left for dead. Paranoia and subservience and cunning are rewarded and the rest is diminished. American boys die every day for a cause they have no stake in. Ronan is so close and I will try to contact him…

I talked to a Brit who wants to work for a human rights group in Palestine but was turned away at the border by Israelis. I talked to a beautiful Japanese nurse who’s made a life in Gaza. She learned Arabic and considers her friends in Gaza like her family. But she’s been barred from Israel as well. Another Brit was four months in Iraq after the war publishing a Baghdad Bulletin.

I am shot through with adrenaline. It is too crazy for words or emotions, and no one can deny it anymore. It is dangerous for us to be here because we know things our governments are trying to keep from us, but even armed with this knowledge I don’t know what I could do in the States. It’s a big ball that’s rolling…

I feel really glad to be here. I feel like I’m in an exciting place at an exciting time, and the situation is terrible, but it’s there, and I am here to learn from it… I have to learn about this kind of thing. ‘Normalcy’ pulls and pulls, and sometimes it takes a blown mind and a broken heart to pull back.

It is difficult to describe what happened that night as I talked to those people… As I heard more and more, my palms began sweating and my heart beat faster, I was almost shaking. My view of the world, which had been teetering precariously on the edge of something anyway, tipped over and crashed, and a vacuum was created. I knew that to fill it was going to be difficult, painful, and exhilarating.I emailed Ronan and told him I was in a neighboring country. I asked if he might be able to get a few days off and come visit me in Amman. He never responded.

Usually when my worldview crashes, the way I see and relate to the world can change so much I barely recognize myself. For me it is one of the most exciting things in the world, though one of the most humbling and exhausting. It has always been well worth it.

So I took a cab to the UN base in Amman and asked if they knew how to contact an Irish U.N. soldier named Ronan in Iraq. They said they couldn’t help me but gave me the email address of some administration that I doubted would be able to do much, either. Somebody asked me, “Do you know his phone number?” I said, “Yes, of course, but…” And then it dawned on me how complicated and obtuse I was being.

I found a cell phone accessories shop nearby. The proprietor said I could borrow his phone and pay for the minutes through him. I dialed Ronan’s cell number. He answered.

“Hi, Ronan, this is Pam,” I said excitedly.

“Hey, how ya keepin’? Call back in an hour or two, OK?” He hung up.

It wasn’t the most romantic first contact, but I wrote in my journal for an hour or two and then tried him again.

This time he sounded happier to hear from me and said that last time his batteries had just run out. I told him I was in Amman, and he told me he was at a U.S. base about as far from Amman as Iraq gets. He said they’d gotten shelled the day before but thank God no one was hurt. They were on coffee break and the bombers missed the mess hall.

His ass was better now and he could sit down again. His unit got ambushed on the way from a town in the south to an American base, and he said he found the smallest rock in Iraq to hide behind. His ass was sticking out, and an Iraqi took a pot shot at it. The blood drained from my face and I thought, fucking hell.

He said his group was acting like police there and it didn’t feel right. This wasn’t the kind of work he had signed up to do, and he felt like he was being used. The Rangers and the Marines were looking out for each other, though. He sounded very discouraged, and he’s a tough bastard, so I figured it was mental rather than physical strain.

I learned for sure that he wasn’t going to be in Ireland in December. It would be three to six months before he got some time off. So I couldn’t visit him after all. I was horribly disappointed but tried to put on a brave face.

I told him about the ‘married Australian’ act I put on sometimes when I didn’t feel like being a single American. I got my ‘wedding ring’ off a Lord of the Rings bookmark. He laughed.

I didn’t tell him that when people asked about my fictitious husband, I described him.

He said he wished he was on my side of the border. I told him to stay safe.

I ended up in a gorgeous hilltop village called Jayyous in the West Bank of Palestine for six weeks instead of Iraq. I had a brilliant time and made some great friends, including a 20-year-old Palestinian who had studied a year and a half in Rostov, Russia. Some of the villagers were fairly conservative, but he and I could talk about anything we wanted in Russian.

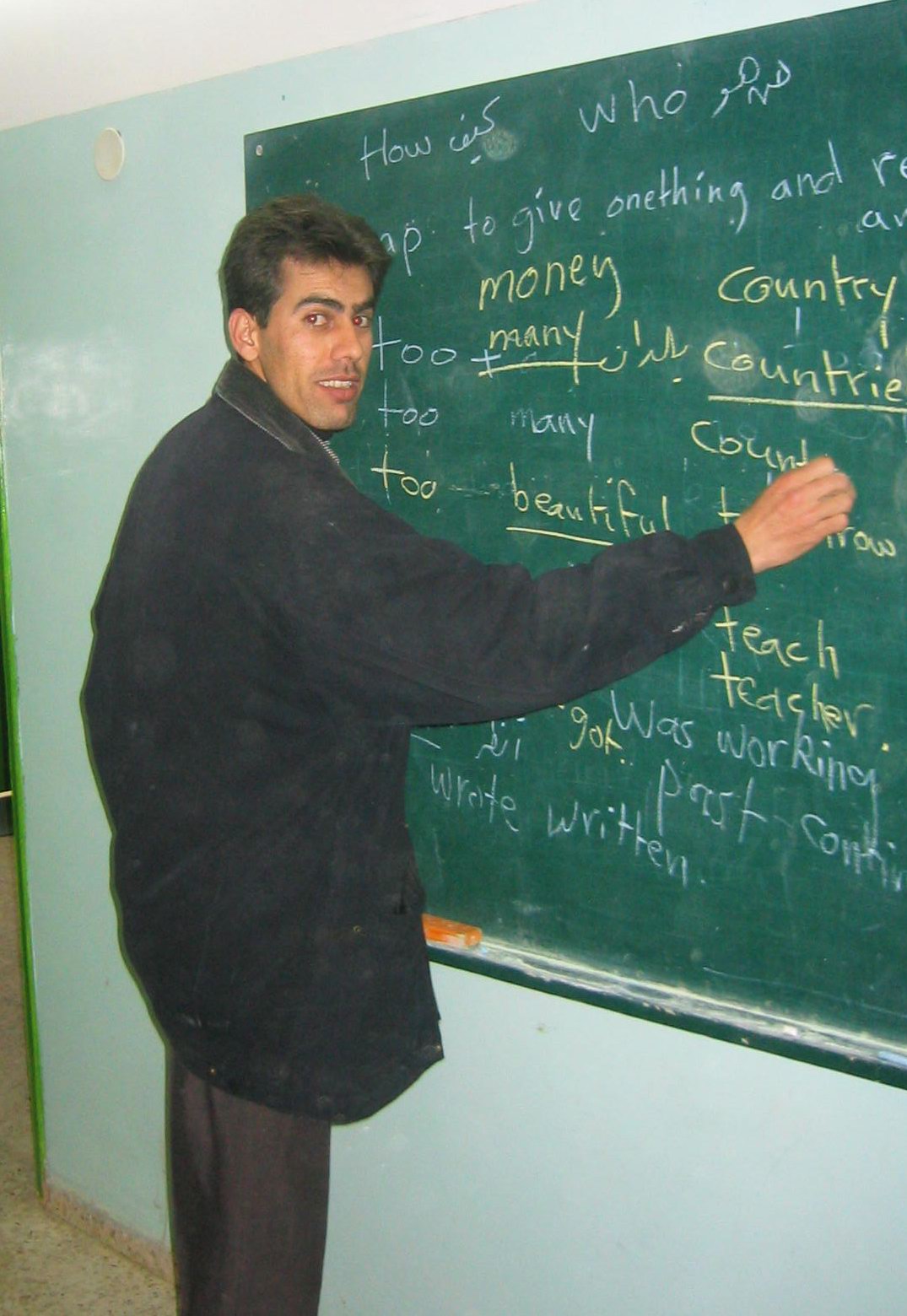

I taught English to smart, funny teen-aged Palestinian girls for a Canadian NGO called Project Hope. A Palestinian woman my age named Abir was my partner, and after class I often secretly shuttled love letters between her and the man she wanted to marry.

I watched CNN and al-Jazeera and smoked nargila and talked for hours almost every night with two brothers named Hakim and Hakam and whoever else happened to stop by. By the time I left the village, I was calling them ‘brother.’

Abir teaching some of the girls

Rasim, another of Project Hope’s teachers

I lived with a family that had two small children, and among our neighbors was the Mayor of the village, a charming old patriarch named Fayez. He had a son my age named Mohamad who was at least as charming as his dad. His daughter, named Azhar, was about 13 years old, and it was strange to see her worried about normal 13-year-old girl things, but also being so strong and brave and kind, and having to face up to all the difficulties her family and village were enduring.

In the six weeks I lived in the besieged village, where people were cut off from their land and water, not allowed to come and go without special Israeli permission, patrolled constantly by armored Jeeps, and harassed in the dead of night by young soldiers, there were no more than two nights that I wasn’t invited to dinner at somebody’s house. Their hospitality was outstanding, and most of their company delightful.

But dispersed among some of the pleasantest hours I’ve spent, I and friends of mine witnessed brutality and humiliation I had not previously dreamt of. Abuses by Israeli soldiers were pandemic and horribly demoralizing. Every time someone left the village, they could be arrested at a checkpoint without charge or trial and held indefinitely, a practice called ‘administrative detention.’ And that wasn’t the worst that could happen by any means. Knowing that my tax dollars were funding the Israeli occupation to the tune of millions of dollars per day for the past 50 years made it even worse.

Ronan, too, had seen the worst brutality done or funded by Western powers in Timor, Lebanon, and now Iraq, and he said it was a shattering bit of education.

Journalists who’ve reported from war zones all over the world say they have never encountered such rough treatment as they are receiving from the Israeli army. According to more than one eye-witness account I’ve heard or read, not counting Ronan’s, children are sometimes shot for sport by IDF forces.

Rachel Corrie, an American activist, was run over by a bulldozer and killed when she tried to prevent the demolition of a Palestinian home in the southern part of the Gaza Strip. A young British photographer, Tom Hurndall, was shot in the neck and killed when he tried to protect some children from sniper fire in Gaza. The Japanese nurse I met in Amman told me about seeing apartment blocks bombed by Israelis with American-supplied jets in Gaza at rush hour, killing children on their way to school under the pretense of ‘counter-terrorism.’

Two of my friends, an American and a Canadian, were arrested without charge by Israeli soldiers and used as unwilling human shields in the town of Nablus, West Bank. They were then taken into an occupied Palestinian home that had been trashed, with feces smeared all over the bathroom, and they were ‘jokingly’ threatened with a loaded machine gun pointed at the American girl’s head.

The leader of a Canadian educational NGO in Nablus, a Palestinian woman in her early twenties, recently had her house occupied and trashed, her little nieces injured by smoke inhalation from the bombs the Israelis used, and an unarmed passerby shot by an Israeli soldier from her own window.

In the West Bank, we saw people’s land and water resources being systematically stolen by what many in the international community call the Apartheid Wall and Israel calls the Security Fence. According to an Israeli source, it is “a 60- to 100-yard-wide combination of barbed wire or chain-link fences, ditches, roads, 25-foot-high concrete walls, concertina razor wire, watchtowers, cameras and electronic sensors” and intended to span 720 kilometers, mostly well within the internationally accepted 1967 borders of the West Bank. (Map of current and proposed layout.) The network of walls and fences cuts Palestinian people off from their land, water resources, families, communities, schools, hospitals, and livelihoods. A town called Qalqiliya with 40,000 residents has a wall as large as the Berlin Wall built all the way around it with only one gate, which is controlled by the Israeli Defence Forces. It has effectively been turned into a giant prison.

Israeli settlements are visible in every direction around the village where I lived, and a Palestinian man I know has sewage from an Israeli settlement regularly dumped into his fields. I had to reassure children when tanks went by their houses, helicopters carrying visible bombs flew overhead, or a car backfired in town. Little boys, with precious little else to do, would sometimes ‘ambush’ armored Jeeps as they patrolled the Separation Fence and throw rocks at them. They usually got tear-gassed in return.

The wife of Fayez, the Mayor of Jayyous, a strong and proud woman, cried like a little girl one day after we had enjoyed a long day picking olives. Nearly every villager who could get past the Israeli checkpoint at the gate of the Fence was there. (Thirteen square kilometers of the villagers’ land now lies behind the Fence on the Israeli side, so now they need special Israeli permission to access their own land.) We enjoyed the day like she had enjoyed it all her life every fall, and her mother’s mother had also, and so on.

Her husband already lost 90% of his grove, about 750 olive trees with an average age of about 600 years old, to the Fence. They were either bulldozed and destroyed, uprooted and shipped to Israel to be replanted, or isolated behind the Fence and de facto annexed by Israel. Now the Fence is cutting people off from what is left of their groves, orchards, greenhouses, wells, and picnic spots, and Israeli pressure to abandon their land is so great that next year she fears nobody will be allowed on the land at all. It will be formally annexed, for all intents and purposes stolen. The mayor’s wife was crying because a delightful, useful, spiritual, communal custom done for centuries could be finished by next season if things continued as they were.

Fayez the Mayor pushing his flirty son Mohamad

away from an Israeli soldier on their own land

The abuses I saw were far too widespread, systematic, and indiscriminate for me to believe they were all and only for Israeli homeland security, nor do I find it likely that the abusers are simply a few bad apples.

I don’t believe Israeli soldiers are worse human beings than anyone else. The Stanford Prison Experiment has suggested that any time a group of people has enormous power over another group of people, an element of personal fear, and a feeling of impunity, the situation tends to lead to abuse and inhumane behavior breathtakingly quickly. Abu Ghraib is a good example of that. After thirty-eight years of building up fear and bad feelings in the Territories, and getting away with more and more abuse, it is not entirely surprising to see things like Israeli helicopters firing into crowds of civilians. It is sobering to imagine what we don’t see.

It is equally sobering to wonder why the leaders of Israel encourage such abuses by routinely letting their men get away with them, and why we in the West allow these atrocities to happen. Our media is severely biased against the Palestinians, and the U.S. government gives weapons and money and bulldozers to Israel and protects them from international accountability. We claim to have gone to war with Iraq because Saddam violated international law and UN resolutions. But Israel is in violation of more UN resolutions than Iraq ever was.

A distraught party leader in the Israeli government has drawn comparisons between Israel’s policies and what happened to his grandmother during the Holocaust. He fears that “At the end of the day, they’ll kick us out of the United Nations, try those responsible in the international court in The Hague, and no one will want to speak with us.” (An Al-Jazeera report Profiles in Self-Criticism touches on the same story.)

Yaakov Peri, one of four former Israeli Security Service chiefs who blasted the Sharon government’s policies, said, “If nothing happens and we go on living by the sword, we will continue to wallow in the mud and destroy ourselves.”

An ultra-Orthodox Israeli Jew named Yehuda Shaul recently returned from his tour of duty as a soldier in the Israeli forces in Hebron, West Bank. As reported in Haaretz, Israel’s left-leaning mainstream news source, during Shaul’s 14 months of service, he could not bear the moral erosion he saw in himself and his comrades. He organized an exhibit of soldiers’ photographs to bring the reality of the territories home. Other soldiers, also mortified by what they had seen and done, offered their photos and testimonies willingly.

Shaul said, “I think that what we’re doing here transcends politics. It’s beyond politics. It’s a true and honest look at reality.”

I consider these men heroes of Israel. They are willing to take a hard look at themselves and their policies and make sincere efforts at improvement. They want to make sure their country is one they can and should be proud of. I admire their courage and hope that they and the people of both sides can band together to educate people, end bad policies, elect better leaders, and make a good-faith try for peace and justice.

I went home in December with my views of the world shaken to their core. The blow to my faith in humanity was offset by the incredible courage and resilience of the Palestinians I’d met, and by the brave Israelis who went against the common thread to protest the actions of their government. I was unutterably horrified, and yet even more inspired.

I decided to spend the summer and fall of 2004 in Ramallah, West Bank, partly because I wanted to help but mostly because I met so many awesome people last time, and I learned so much and had such a great time. I thought the culture and lifestyle I saw being systematically destroyed was worth preserving, and I wanted to enjoy it for myself while I could. I hope it will be there for many more generations to come.

I will work with al-Mubadara, the Palestinian National Initiative, Palestine’s democratic reform party. The leader of the Initiative, Dr. Mustafa Barghouthi, is a Palestinian who was trained as a medical doctor in the former Soviet Union, received a Masters degree from Stanford University, and has had an outstanding humanitarian career. The Initiative seems to me like the best hope for accountable leadership in Palestine, which I hope can lay a groundwork for peace and democratic nation-building, so people can get on with life.

I couldn’t wait to talk to Ronan again. I had a few stories of my own to tell, and I ached to hear more of his now that I knew more about occupation in general and the Middle East in particular. He knew so much more than I did, and I knew he’d have crazy stories from Iraq. Anyway I hoped he’d be proud that, largely because of him, I’d stumbled into my own international issue.

When I got home to Oklahoma, I wrote to him that I hoped he was OK, and maybe I could visit him in Ireland after I left Palestine this time. I tried to call him several times in January and February, but only got his voicemail and was never able to get in touch.

On March 10, I wrote him again: “Hey Ronan, still alive? Call or write sometime…”